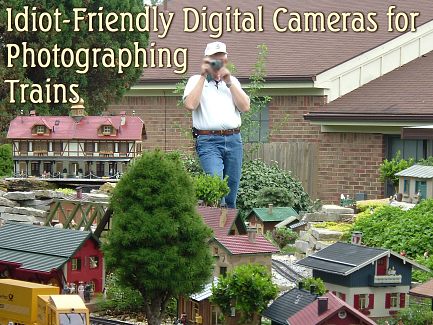

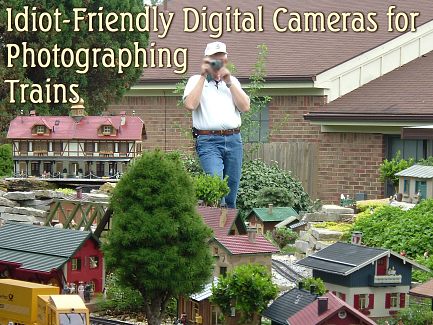

Idiot-Friendly Digital Cameras for Photographing Trains - Updated for 2016! Idiot-Friendly Digital Cameras for Photographing Trains - Updated for 2016!

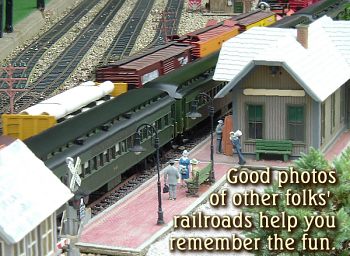

Digital cameras are great because you can fill your memory card with photos, and only print out the ones you like. That said, many folks have come home from an open house or train show to find that particular photos they really wanted to have didn't come out the way they wanted (even though they looked fine on the LCD). But people who invest in "better cameras" may have even worse luck than people who buy "point and shoot" cameras, because they have trouble learning (or remembering to set) all the various settings for each situation. Another potential disappointment is when a "killer" photo that looks great in on the computer screen or in a 4x6" printed photograph looks "washed out" or "soft" when you try to print it any bigger.

Quickie Recommendations for 2016

If you want to know, here's a "quick and dirty" list of things to look for:

For convenience and a higher proportion of good shots either outdoors in bright sunlight, or indoors in lower poor light situations, consider a camera with the following features:

- Ability to run on AA cells - AA cells are available anywhere, and it's still possible to get good NiMh rechargeables (try to get something in the 2300-2500 mah range). Cameras with "proprietary" batteries that you have to recharge between uses can be inconvenient when you're on a long trip or "out and about" away from an AC outlet to recharge the battery for a long time.

Note about AA cells in 2016: Department stores like Target and WalMart that used to carry 2300 and 2500mah AA cells and heavy duty chargers now carry only 1600mah batteries and weenie chargers that lack things like auto-shutoff when the battery is charged. So shop carefully.

- Image Stabilization - This doesn't work miracles but it helps reduce the wobble, including the wobble that comes when you push down the shutter button. Cameras with 10x zooms or longer may advertise something like "dual" or "ultra" image stabilization. That's even better.

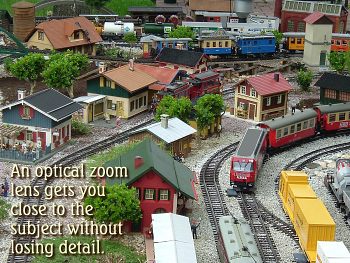

- Decent Lens - Most cameras that have a 6x or better lens will take substantially better photos in borderline situations than 4x lenses because the bigger lenses let in more light, even if you don't have the zoom on. Also, if the lens has a separate brand name like Schneider-Kreuznach or Carl Zeiss or something, that should indicate a better lens as well.

- Viewfinder - Sadly, most otherwise "decent" cameras under $300 have opted to replace the viewfinder with a larger LCD screen. True, that may help you get better shots of the drummer from a mosh pit (because you can hold the camera way up in the air when you take the photo). But outside in bright sunlight, that LCD screen may be almost useless. On the other hand, if two cameras' specs are similar, and the one with a viewfinder costs twice as much as the one without a viewfinder, it's your call. Chances are, the one with a viewfinder has other pro features that will help you take better photos with it. BUT a lot of $150 cameras today compete with the $400 cameras of a few years ago in quality because of improved resolution, light sensitivity etc. So don't feel bad about going for the lower cost - just don't buy the cheapest possible camera and say I told you to.

- Live Update and Video Recording - These refer to the ability to use the LCD screen to frame your shots, as well as the ability to capture videos. Yes, almost EVERY pocket camera with an LCD screen has those now. But not all SLRs (the big cameras with the swappable lenses) have them.

If you're looking to upload videos of your train to YouTube, a camera that does 720p resolution videos will still do the job. However, if you're looking to upgrade digicams anyway, you may notice that some of the better pocket cameras now have 1080p video recording. Again, a crap lens will make resolution figures meaningless, but a good lens and high resolution are worth considering.

- Pull-Up Flash - Even my cheapest camera I use all the time (an old Canon PowerShot SX150) has this feature, which makes life a whole lot simpler if you do a lot of indoor photography. I almost NEVER use the flash. In the past 12 months we have toured several national museums where we were allowed to take photos as long as we didn't use the flash. Indoor railroads, the same. I stand as still as I can, and shoot. Most of the time I get a good shot indoors. Not to mention that photos taken in natural lighting - as long as they come out at all - are far nicer than photos taken with a flash.

You WON'T get a good indoor photo of a train speeding by or your dog or child jumping up and down. But the inconvenience of having to flip up the flash once in a while is greatly outweighed by the convenience of knowing that the flash isn't going to come on automatically (like it does on most cameras without this feature) and blind people, draw attention to yourself, or get you kicked out of a museum or special event.

History - I started taking lots of digital photographs other folks' railroads in 2005, after a publisher criticized me for not having a stash of photographs ready to send to him for approval with something I was trying to get published. My first digicam - a 2-meg Fuji with a 3x lens (A205) didn't do well lighting was poor, or it was too crowded to get the best distance from what I was trying to shoot. Yes, many of you have cell phones with better cameras today, but this was a while back . .

I upgraded to a Fuji E-550 which had a 6.3 meg "super-CCD" sensor and 4x optical zoom. I got a lot of good photos with it - indoors and outdoors - before the lens locked up and I sent it back to Fuji who (I discovered later) lost it (though they made it right eventually).

Eventually I got tired of waiting for word on my Fuji, and I didn't want to go through that Christmas without a good camera, so I bought (on a closeout sale) a camera that as most of the "idiot-friendly" features I commented on earlier, a Canon A720 IS. Its "image stabilization" feature gave me better photos in borderline situations than the Fuji. Years later, one of my kids took it on a zoology field trip to Mongolia and took hundreds of great photos with it. Eventually I got tired of waiting for word on my Fuji, and I didn't want to go through that Christmas without a good camera, so I bought (on a closeout sale) a camera that as most of the "idiot-friendly" features I commented on earlier, a Canon A720 IS. Its "image stabilization" feature gave me better photos in borderline situations than the Fuji. Years later, one of my kids took it on a zoology field trip to Mongolia and took hundreds of great photos with it.

Later I found a Canon A-530 on closeout and picked it up just to have an extra camera around - it seemed that every time I took my A720 out of the house, somebody needed "the" camera for some reason. The A-530 lacked any kind of image stabilization, but worked for most of the casual uses it was put to - mostly trips to the zoo and such. Later I found a Canon A-530 on closeout and picked it up just to have an extra camera around - it seemed that every time I took my A720 out of the house, somebody needed "the" camera for some reason. The A-530 lacked any kind of image stabilization, but worked for most of the casual uses it was put to - mostly trips to the zoo and such.

Then we learned that Fuji had lost my E-550 and were afraid to admit it. So they sent me a Fuji E-900 instead. It had better resolution, than the Fuji E-550 but it still lacked image stabilization, as did most Fujis under $300 until about 2008. It was okay, but the Canon A-720IS generally took better photos in low light. me a Fuji E-900 instead. It had better resolution, than the Fuji E-550 but it still lacked image stabilization, as did most Fujis under $300 until about 2008. It was okay, but the Canon A-720IS generally took better photos in low light.

Current Cameras

In the meantime, I had been watching the Canon SX lines of cameras carefully, hoping to catch one on a closeout. The SX 10, 20, 30 and so forth cameras were built like mini-SLR cameras. I had no reason to believe they'd be as good as my friends' digital SLRs, but I knew with the big honking lenses they'd be better than any camera I'd bought so far. The SX 120, 130, etc. has similar specs, but smaller lenses and no viewfinder or slot for a flash attachment, which reduced the cost by $150 but made them less interesting to me.

That said, about 2011, I saw an unpriced Canon SX 20 in a glass case at a Meijer store. By then, the camera was two versions "old," but it still had better specs than any camera I'd owned so far. So I had the sales guy scan it. It came out to about $100, a quarter of its original price. As far as I could tell, someone had bought it, looked at the instructions and returned it, and it had sat on a shelf in a back room for the next two or three years, while the closeout price kept getting lower and lower. That was a no-brainer. I've taken lots of great photos in some very difficult lightng situations - and even taken a few from the window of a moving train that came out pretty clear. Based on my experience with this camera, I'd recommend any camera in this line to anyone interested in the best camera they can buy without stepping up to an SLR. That said, about 2011, I saw an unpriced Canon SX 20 in a glass case at a Meijer store. By then, the camera was two versions "old," but it still had better specs than any camera I'd owned so far. So I had the sales guy scan it. It came out to about $100, a quarter of its original price. As far as I could tell, someone had bought it, looked at the instructions and returned it, and it had sat on a shelf in a back room for the next two or three years, while the closeout price kept getting lower and lower. That was a no-brainer. I've taken lots of great photos in some very difficult lightng situations - and even taken a few from the window of a moving train that came out pretty clear. Based on my experience with this camera, I'd recommend any camera in this line to anyone interested in the best camera they can buy without stepping up to an SLR.

One of my other daughters was going to Ireland for a semester and wanted to take a good camera. It so happened that right before Christmas, the Canon SX120IS went on sale for $100. So it went into her stocking. It lacks a viewfinder, but is a bit smaller than the SX20IS, so she was able to drop it into her purse or coat pocket. The photos from that camera were so close to mine in quality I sometimes had to check the "properties" of a photo to see which camera it was taken with. Also, during the trip to Ireland, the SX120IS was dropped badly twice. The first time made the battery door a little flakey; the second time knocked out some pixels in the viewfinder, but it still works. One of my other daughters was going to Ireland for a semester and wanted to take a good camera. It so happened that right before Christmas, the Canon SX120IS went on sale for $100. So it went into her stocking. It lacks a viewfinder, but is a bit smaller than the SX20IS, so she was able to drop it into her purse or coat pocket. The photos from that camera were so close to mine in quality I sometimes had to check the "properties" of a photo to see which camera it was taken with. Also, during the trip to Ireland, the SX120IS was dropped badly twice. The first time made the battery door a little flakey; the second time knocked out some pixels in the viewfinder, but it still works.

When the SX-150 went on sale for $100 on closeouts, we bought three - one to replace the broken SX-120, one for me to use as a "pocket camera," and one for my other daughter whose camera had given up the ghost. All of those cameras are in use today.

Canon later upgraded this to the SX160 and 170, but they seem to have discontinued that line in favor of upgrading the SX-4XX and SX-5XX lines. Those lines have similar specs but no viewfinder. But any camera in either line will take WAY better photos than the average point-and-shoot digital camera of just a few years ago. Sorry I can't be more specific. Also, I haven't gone shopping for other brands for several years, because the cameras we have do a fine job.

Note About Video - If video is important to you, the Canon SX530 now takes 1080P video, which is better than the 720P videos that the older lines take. Several of the newer lines also have WiFi, which makes uploading photos to your computers or your friends' computers easier.

now takes 1080P video, which is better than the 720P videos that the older lines take. Several of the newer lines also have WiFi, which makes uploading photos to your computers or your friends' computers easier.

Why I Need "Idiot-Friendly" Gear - A few years ago, a friend told me he liked a particular piece of electronic equipment because it was "user-friendly." Bewildered by the array of controls and settings on that piece of gear, I said, "I must need something that is 'idiot-friendly,' then." The good news about digital cameras is that the better cameras are becoming more "idiot-friendly" every year. For example, the "automatic" settings are getting better at getting the best shot of whatever you have framed.

In "normal" conditions, a decent "idiot-friendly" camera will give you more good shots than most inexpensive digicams. But in "difficult" conditions, say, where the camera must compensate for distance or poor lighting, an "idiot-friendly" camera will get shots that you couldn't get otherwise period. To discuss digital cameras (and "idiot-friendly" features) intelligently, though, it's important to understand a few factors that can improve or hurt your ability to get attractive, useful photographs under a wide range of conditions.

What Features Are Important? Most people who advertise digital cameras discuss the "resolution" of their product above everything else. And if all other things were equal, a 12-megapixel camera would outperform an 8-megapixel camera. But all other things aren't equal. Cameras also differ in lens quality, operating speed, optical zoom, low-light performance, and other "user-friendly" features such as "image stabilization." As an example, an 8-megapixel camera with a good lens will consistently provide a higher proportion of good shots than a 12mp camera with a cheap lens.

That said, resolution is an important issue. Digital cameras are measured in "pixels." These are a little like the dots on a printer in that each pixel can be a different color. But they don't correlate entirely to dots on the printer, because "pixels" in a digital photograph are "run together" in the print process to give a smooth-looking photograph. So, a color printer set to 200dpi will produce a poor printout of your resume, but may produce a bright and smooth photograph at the same setting (if you use the right paper). Nevertheless, if you are taking photographs to blow up or to use in books or magazines, you will do better with a higher resolution camera, all other things being equal. Also, high-resolution photos are more forgiving about "crops." For example you may have a photo of a group of people but want to print a photo of only one person. The higher the resolution, the more likely it is that a photograph printed from a quarter or eighth of the original photograph will be useable.

A Note About Continuously Increasing Resolutions - As digital cameras continues to flood the market, you'll notice that resolutions keep increasing, especially at the "low end." About 2000, 2mp cameras were "standard" at the low end. By 2006, 4 mp cameras were "standard." By 2008, 10mp cameras were becoming "standard," and many inexpensive 12mp and even 14mp cameras were becoming available. This is due to the huge competition among vendors, and the fact that once you've developed a 10mp sensor you can mass-produce, it doesn't make any sense to tie up your facilities producing 8mp sensors. That said, some reviewers have noted that photos produced by some new 12mp sensors are no sharper or more colorful than the 8mp versions. When I wrote the first version of this article, it was almost impossible to get an 8mp camera for less than $400. Now that 8 and even 12mp sensors are advertised in $99 cheapies, it is becoming even more apparent that the quality in these cameras is not limited by resolution so much as it is by the quality of the lens and the camera's internal mechanism and software.

Another consideration is that higher resolutions mean that the photos will take up more room on your hard drive. Will it really benefit you to fill up your hard drive with 4-meg files from a 12mp cheapo, that are actually less useful than the 2-meg files from an 8-meg camera with a good lens? Also worth noting is that MOST cameras under $600 use a sensor that is only about the size of the fingernail on your little finger. To increase advertised resolution, manufacturers are squeezing more and more circuitry onto the same "real estate," with diminishing returns. As an example, in most "everyday" uses, my old Fuji E550 6.3 meg camera took sharper photos than my newer 8mp Canon A720 IS. In difficult shooting situations, though, the Canon was better, but that was due, not to resolution, but to a bigger lens, better low-light-sensitivity, and image stabilization.

A Note About Sensor Size and DSLRs - Since we've mentioned sensor size, let me add that entry-level "Single Lens Reflex" digital cameras (DSLRs) have a sensor that is about the size of your thumbnail, about four times the size of the sensor in "consumer" cameras. The sensors in Sony's NEX cameras are about the same size as well. That means that each sensor has that much more room to collect light without noise-causing digital glitches. In addition, the larger sensor requires a larger lens, which lets in more light and allows faster shutter speeds. Is it any wonder that a 10mp DSLR will produce a sharper, more colorful, more useful photo than an 12 or even a 14mp consumer camera? If you go to a DSLR, you usually give up some ease of use and some "user-friendly" features. But in case you wondered, there IS a significant difference, between the output of even today's low-end DSLRs, and the output of the best "DSLR-like" consumer camera.

If you don't want to learn photospeak and drag around a big camera, that's okay - 95% of non-professional digital camera users are more than satisfied with the features and performance of the best current non-DSLR cameras.

A Note About File Formats and Memory Cards - Most digital cameras save their photographs in a format called JPG onto memory cards that can be removed. JPG is a graphic file format that "compresses" the file to save memory. As an example, if a section of blue sky is almost all exactly the same color, the software that creates the JPG file will make it all the exactly the same, so it can save space when it writes the file. The "higher" the compression ratio, the more compromises JPG makes with the original digital information. Still, most photos can stand a little compression, and this saves a great deal of memory. For example, files from my 12mp camera are actually under 4meg, although if I saved with less compression, they could be as big as 6 meg. The good thing about compression is that I can get three times as many photographs on the same memory card, and JPG files are fast to save and copy. JPG files are also very portable; they can be used on every kind of computer, shown on many DVD players, and so on. But JPG compression has one disadvantage; every time you open and save a JPG file, the software "recompresses" the picture again, and you lose a little more detail. If you plan to "tweak" and "crop" your photos, save your original JPG files in one directory (or burn them to CD) and use another set of files for your editing; otherwise, after opening, tweaking, and closing a file more than a few times, you can wind up with a file that is not nearly the quality you started with.

If you need the best possible image, some cameras give you a choice of a high-resolution JPG format (usually called "fine" or "superfine") that uses minimum compression. But if you want to guarantee the maximum resolution of a photograph, say because you need it for archival purposes or to send to National Geographic, you may want to look for a camera that supports the RAW or TIFF file option. The disadvantage of using non-compressed files is that you'll use up your camera's memory card quickly, as well as your computer's hard drive. As an example, an 8-megapixel camera saving RAW or TIFF files may save 8-meg files (or larger), while the "fine" version might be only 4-meg, and the "normal" version might only be 3-meg or less. Two side effects of this difference are:

- Large RAW or TIFF files take longer to write to your camera's memory card, so your camera can get "backlogged" and you'll miss shots.

- An 8-gig memory card that can hold 2496 "normal" JPG files from an 8-megapixel camera will only hold 640-1000 RAW or TIFF files. That's the main reason that people who take digital photographs for publication also buy big, fast memory cards.

Another memory card consideration is memory card type. There used to be several options, including Secure Digital (SD), Compact Flash II (CF2), Memory Stick Pro (Sony), and XD Picture-Card (Fuji and Olympus). Nowadays most cameras use SD cards, but they vary in quality and size. If you plan to use your camera for movies or taking a lot of photos quickly at a sporting event, try to find the fastest SD card you can for the money.

Lens Quality - Okay, that's easy; get a 10-megapixel or better camera and lots of memory, and you're home free, right? If you're only going to shoot stable images in bright light, yes. But if you need to take photos of moving objects (like trains) or you may be taking photos in less than optimal lighting (say in train sheds or under shade trees), the lens quality may make more difference than the resolution of your camera. An 8mp photo taken with a very good lens may be more useful when enlarged or published than a 14mp photo taken in dim light or with a poor lens. How can you tell if you have a good lens? A few basic comparisons may help:

First of all, don't bother with any camera that does not have an optical zoom of some sort. Digital zooms work by letting you reduce the resolution of your photograph so it "feels" like you're zooming in on the subject when you're really only cropping out most of the frame (and "wasting" most of the resolution of your sensor). First of all, don't bother with any camera that does not have an optical zoom of some sort. Digital zooms work by letting you reduce the resolution of your photograph so it "feels" like you're zooming in on the subject when you're really only cropping out most of the frame (and "wasting" most of the resolution of your sensor).

Next, most consumer-oriented cameras with telephoto lenses (say 6x to 12x optical zoom) have better lenses than cameras with just 3x-5x zoom, especially if you reserve the greater magnifications for use outside in the sunlight. As basic as this may sound, a bigger lens lets in more light, especially at moderate zoom settings, so the camera can get "what it needs" quicker. The shutter isn't open as long, and the sensor picks up less "noise" from the optics and less "blur" from the way the camera is being handled. And, of course, being able to really zoom in on your subject from across a pond or a railroad yard or bridge is a very good thing, too. It will allow you to get shots you couldn't possibly get otherwise.

You might look for a brand name on the lens that is different from the brand name on the camera. For example, better Kodak cameras often have Schneider-Kreuznach lenses; better Sony cameras often have Carl Zeiss lenses, and so on. That doesn't mean that a 3x Schneider-Kreuznach lens will necessarily outperform a 12x "generic" Kodak lens. Rather it means that if you're comparing two cameras with similar specifications and features, a "name-brand" lens may indicate better quality.

Sometimes the marketing materials for the camera say something like "all glass, aspherical." That's good, too, especially if you're comparing two similar cameras and the other camera doesn't say anything about the quality of the lens.

Another issue that used to be a consideration is called a "macro" function, the ability to reset the camera so that you can get a closeup shot within an inch or so. This is great for taking close-ups of model trains, especially when you want the model not only to fill the frame, but also to have the same perspective as you would get if you were photographing the "real thing" up close. I say that it used to be a consideration, because most digital cameras over a $100 today have a good macro function, and most of the better digitals have a great macro function.

Time Between Shots - Another issue is how fast the camera focuses and shoots - a camera that takes a second or two to reset and refocus between shots, or that takes a second to fire after you press the shutter button means that you will miss shots when the subject is moving quickly. Fortunately, digital cameras are getting faster all the time, but it's also a fact that the more expensive cameras tend to be faster (in some cases much faster) than cheap ones. Ironically, when I got my SX20IS, it took longer between shots than my smaller cameras. It turned out that there was a "review setting" that specified how long a photo you snapped would stay in the viewfinder to give you time to evaluate it. The default was two seconds, which isn't bad for portraits, but it made taking pictures of moving trains or flying birds pretty tough. When I set it to zero, certain other features didn't work, but the half-second setting is a good compromise.

Camera "Line" - Within most brand names, you'll notice different lines. For example, Fuji has an A line, an E line, an S line and so on. Canon has an A line, a G line, and S line, and so on. The A lines tend to be targeted to consumers who want the simplest, lightest, least expensive camera available with decent resolution and optical zoom. As a result of the smaller size and reduced price, they often have slower mechanisms and cheaper lenses than the other lines with similar features but higher prices.

Low-Light Handling - If you're an old time who used to like to take 35mm photos without flash in dark rooms, you are used to buying ISO 800 or 1600 "fast" film. If you weren't able to adjust the sensitivity of the film (say, you had just loaded a roll of 200 film), you had to adjust in other ways, such as using the tripod so the fact that your shutter was open a ridiculously long time wouldn't introduce blur into the equation. Until about 2011, most digital cameras haven't handled low light as well as you'd think they should for the price. And the maximum sensitivity setting (which was seldom above ISO 400 equivalency) usually gave you photographs with a lot of weird dots and other artifacts that photographers call "noise." Today's sensors are getting better, and having a state-of-the-art sensor behind a really big lens helps a lot.

You may not have realized it, but the "auto" setting on your camera is constantly adjusting the ISO setting. But having a camera that advertises an ISO setting of 800 or above at least gives you some options. In addition, "image stabilization" and similar features (see below) can help you get clearer shots in low-light situations where the shutter has to remain open longer than "optimum."

Viewfinder Choices - Many companies are removing viewfinders from their mid-line digital cameras. After all, most people use the LCD screen on the back most of the time. But when you're outside in bright light shooting into shade, a viewfinder is invaluable. I still prefer having viewfinders of some sort, whether they're "optical" viewfinders that simply show a real-world view that approximates what the lens is seeing or "digital" viewfinders that show a reduced version of what you're already seeing on the LCD screen. Sadly, most otherwise decent intermediate cameras have removed the viewfinder altogether, simply making the lcd on the back bigger. Yes, that's great for getting snapshots of the lead guitarist from the mosh pit, but it's not as useful outside in bright sunlight as you'd think.

Idiot-Friendly Design Features - The other major consideration (besides resolution, lens quality, time between photographs, and low-light handling is how "idiot-friendly" the camera is. Photography buffs want to be able to set all the parameters for each exposure by hand; professional cameras allow that, and so do many "semiprofessional" cameras. Cameras made for amateurs also typically have several "automatic" settings for what is called "point and shoot" operation. So the photography nuts in the family can fiddle to their heart's content, but the other family members can choose an automatic setting, then "point and shoot" and get a high percentage of good photos.

Image Stabilization - Since I wrote the original article, image stabilization has been finding its way into smaller and cheaper cameras, so it's worth pointing out that image stabilization does not compensate for an undersized lens or poor light sensitivity. If you are choosing between two similar cameras, and one has image stabilization and the other does not, go for the one with image stabilization. But don't expect it to work miracles, or to compensate for rapid object movement - it won't.

Idiot-Friendly Software Features - One place where I draw the line is on software that keeps me from using the camera the way I want to. Most digital cameras allow you to plug in a USB2 cord between the camera and a PC, then read the camera memory from the PC like you would a portable "thumbnail" memory card. If you do this, you need to remember to download the photos to the computer's hard drive before you start editing them (or even "rotating" them to view properly, which is a kind of edit). Otherwise, you may create glitches in the camera's memory card and have to reformat it to get it to work properly again. You also want to use the camera's buttons to delete photos, not your computer, for the same reason. Once you realize that, you can easily take a digital camera and the supplied USB cord all over the world, downloading photos on other people's PCs and Macs to your heart's content.

That was why I had a problem with early Kodaks, which would not let you download photographs to your PC without loading the cumbersome "Easy-Share" software on every PC you planned to attach the camera to. Nowadays Kodak isn't making cameras, so Easy-Share isn't an issue. However if you're a complete beginner on computer and your camera comes with "sharing" or "library" software that you find helpful, that's fine.

What About Cell Phones?

I now have a smart phone that has a bigger photo sensor than any of my first five digicams. However it has a lens shaped like a BB. So it's fine in well-lit situations like daylight zoo photos. Or group selfies at a pizza parlor. But not for demanding photos that you may want to blow up. Once my camera batteries ran out in an indoor situation and I had to use my smart phone to record an event that was indoors surrounded by windows on a sunny day. ANY of my digicams from my Fuji E-330 on up would have done a fine job, because of the decent lens. But the digital artifacts on the photos I took with my smart phone kept me from blowing any of them up the way I usually would.

Overall Choices (Updated for December, 2016)

When I first wrote this article, there were about fifteen recent entries worth writing about or checking out. Since then, about 600 new models have been released. At this point, I can't keep up, and any list I provided today would be out of date in a month. So instead of listing specific cameras, I'll just list classes of cameras and features you should consider.

- Pocket Cameras - Good - If you want a decent, handy camera that you can fit into a purse or Dockers pants pocket, look for:

- Pixels above 8 meg

- AA -battery powered

- Optical zoom up to 8x if possible (the higher the optical zoom the better all of your pictures will be, so take that into consideration)

- ISO rating up to 800 (if ISO isn't listed ANYWHERE, don't bother)

- Aspherical, all-glass lens, with a name brand lens being even better.

- Flip-up flash, which keeps the flash from coming on automatically where you'd rather not use it.

- Big Zoom Cameras - Better - If you are okay with a camera that has a fairly large lens and looks like a miniature DSLR camera, you have several excellent choices. Consider:

- Pixels above 12 meg

- AA -battery powered

- Optical zoom 12x or higher (the higher the optical zoom the better all of your pictures will be, so take that into consideration)

- ISO rating 1600 or higher (if ISO isn't listed ANYWHERE, don't bother)

- Name-brand lens

- Flip-up flash

- Digital Single Lens Reflex Cameras - Best - If you'd like to investigate DSLRs, Canon, Nikon, Olympus, and Pentax all have "entry-level" DSLRs that will outperform any of the one-piece cameras on this page. You'll notice that most of the "specs" I list are the same as the big zoom cameras above. The real difference is the size of the sensor and the ability to swap out lenses for specific purposes.

- Pixels above 12 meg

- AA -battery powered

- Stock lens that goes up to 55mm or more (these will typically give you an optical zoom comparable to 12x)

- ISO rating 1600 or higher

Conclusion

So if you're thinking about a trip or a special event, (especially if it's the next Large Scale Convention or garden railroad open house), think about getting a camera that will bring back a visual record that you can treasure the rest of your life. Be sure to buy your camera a few weeks or months before the trip, though, so you can get used to using it, and so you don't have to spend the first night of your vacation trying to figure out how to get the memory card in or something.

Paul D. Race

P.S. In case you wondered, the man in the title photograph is not an idiot. He is a good friend, a very good garden railroader, and a great person, who, thankfully, also has a sense of humor.

|

|